Last April, more than 1,000 college and high school students descended on the Motor City to participate in a very special competition, the Shell Eco-marathon. For more than 30 years, the competition has challenged the minds and talents of future automotive engineers to push the limits of automotive design. Not with speed or endurance as the final goal, but fuel efficiency as the primary objective. The team with the best fuel efficiency (miles per gallon equivalent) wins.

The 2015 event marked the 9th edition of the Shell Eco-marathon Americas and the first year for the event in Detroit. It was one of four world events held in 2015, with similar competitions in Europe, South Africa and Asia. The Americas event hosted teams from 100 different colleges and high schools (as the name suggests) from North, Central and South America. And while there were awards presented for off-track accomplishments like vehicle design and technical innovation, the real bragging rights would come from victory on the 0.9 mile track that wound through downtown Detroit, starting and ending in front of the Cobo Center.

There are two basic classes teams could enter — Prototype or Urban Concept. Prototype entries were designed primarily for ultimate efficiency and design, and can have three or four wheels. Urban Concept is a bit more challenging, requiring four wheels and all the related accessories needed to be “street legal.” In addition to the two basic categories, each class is further broken down into the type of propulsion system used: gasoline, diesel, hydrogen fuel cell, or battery/electric.

The high mileage winner was the team from the University of Toronto, besting defending champs from the Université Laval, and posting a winning efficiency equivalent of 3,421 miles per gallon in the Prototype Gasoline class. And while these two schools have been close competitors the last several years, there is an even more exciting story I’d like to share with you.

A little town in Colorado

Roughly 1,300 miles to the west of Detroit is the small city of Wheat Ridge, a suburb of Denver, Colo. Sixteen-year veteran Wheat Ridge High School teacher and coach, Charles “Chuck” Sprague has been teaching drafting for more than 13 years and over that time, and with a little help from good friend Doug Gallagher, the projects his classes have taken on have continued to increase in scope and challenge. A little more than a year ago, Sprague took on the school’s STEM/Engineering program. STEM stands for “Science, Technology, Engineering and Math” and is a whole lot more than the shop classes we took when we were kids. The program was brand new for the 2014-2015 school year and Sprague tells me that, “I wanted to do a completely ‘outside the box’ type class.”

Many successful high school engineering programs use already created project kits, and Sprague admits that these kits are excellent ways for students to learn fundamental engineering principles. But that wasn’t quite what Sprague had in mind for his students. “I wanted to get away from that and start at ground zero. I wanted to show the students the entire process from beginning to end of a large open ended project.” But what kind of project?

Sprague tells the story this way: “Doug (Gallagher), along with Dr. Ron Rorrer from the University of Colorado — Denver asked if they could speak to my class to see if they would be interested in the Shell Eco-marathon. If there was enough interest we would proceed with their help and create a partnership between Wheat Ridge and UCD. If there weren’t enough interest then it wouldn't happen. After their presentation was done, 16 students’ hands shot straight up in the air, and we were off and running with this very unique and new model between a high school and a university.”

“As a side note, the students came in the next day and asked me what they do next. I looked at them shrugged my shoulders and told them, ‘Well, you guys decided that you wanted to build a car from the ground up. I am here to help answer questions and guide you when you need help. But you all voted to do this project. So you better start working on it.’ There was total silence as they waited to see if I was kidding. I just sat there.”

The idea of building a competitive Prototype-class, hydrogen fuel cell-powered car from the ground up may have sounded exciting in the beginning to the 16 young men and women that would be taking on the challenge. Little did these students, some just starting their high school adventure and some entering their last year, know just how much of a challenge it would be, nor could they anticipate the obstacles they would have to overcome on their way to Detroit.

The next 8 months

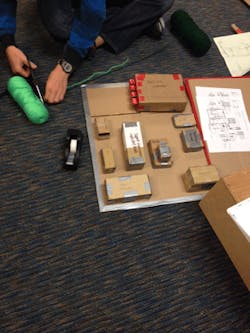

“The design process starts on the computer,” shares Sprague. “Then the students have to take these designs and manufacture the molds and additional components (for the car). We also created small engineering groups within the class with each responsible for a different section of the car. They had to learn to work together just as they would in a small company, complete with collaboration, brainstorming sessions, problem solving and even resolving personality conflicts once in a while.”

“Designing it on a computer and then trying to build it doesn’t always work quite the way you think,” observed Gallagher. That was OK for most of the students, though, since none of them had any prior experience in doing either. And even though the design segments were separated within the group, everyone helped everyone else. “It was a team effort all the way around,” according to Sprague.

The design phase took the students a full two months to complete. The next phase was to share those designs with computerized milling equipment, starting with the building of the car’s body using carbon fiber as the shell. Then freshman Jacqueline Pedlow helped lead the team in this phase of the project. She explained the process for making the body mold in a live video interview I did with the students still attending Wheat Ridge.

It starts with large foam blocks used to build a mold slightly larger than the designed body. A CNC mill is used to cut the foam blocks to the exact shape of the body, in sections and stacked, that becomes the mold for laying out the carbon fiber material. This final foam mold is sanded and smoothed. Any imperfections are filled and the mold is sanded again to prevent any bumps or surface irregularities in the final product.

The mold is then coated with a wax and release agent before the first carbon fiber cloth layer is applied. An epoxy hardener is applied to each custom cut sheet before it is placed on the foam skeleton. After all the layers are applied, a release sheet and breather sheet is then placed over the body, and the whole thing is placed in a vacuum bag and a vacuum applied. The mold sits for 24 hours to cure and then the hardened carbon fiber is popped from the mold for assembly.

The entire milling of molds and carbon fiber process took the students approximately 3 months to complete and then it was on to the actual build. If you’ve ever built your own race car, hot rod or restoration, then you have some idea of what these kids had in store for them. They had to design and build the chassis components, manufacturing what they couldn’t out source. The vehicle’s electrical and propulsion system had to be designed. And the entire thing had to be assembled by hand.

All with the goal of energy efficiency, meaning every aspect of the design had to be weighed against its impact on overall weight and aerodynamic impact. Even the selection of the driver had to be carefully considered, with those duties eventually falling on the shoulders of Nicole Ortega, currently a senior at Wheat Ridge and member of the team for their 2016 run. How did she become the driver? “Girls’ weights don’t tend to fluctuate as much as guys do in their high school years,” Ortega told me. That makes sense, and just shows how much thought and energy these young students were putting into their project.

The entire project took roughly eight months to complete. Eight months of late nights, long weekends, lots of fundraisers, corporate presentations and overcoming one challenge after another. Unfortunately, there would be additional obstacles placed in their way.

One week to go

With the car built and one week left to go before the competition in Detroit, test runs began. The team was limited to testing in the school parking lots and they weren’t sure how that would relate to the hills and turns they would face on the downtown Detroit streets. But Sprague shares the story of the last major challenge his team had to overcome.

“We tested the car out front (of the school) between 10-11 p.m. with only the parking lot lights to light our oval course about three days before the competition. We were checking the speed and we weren’t going to be able to finish the track in Detroit in enough time (seven laps of the 0.9 mile course had to be completed within 25 minutes). So the next morning I started calling around to see if I could locate additional fuel cells, maybe even buy one if needed. The kids put so much into it, the car was ready, but we weren’t getting enough power.”

“These cells aren’t something you can buy off the shelf. It normally takes a few months to get one to you, let alone two days. I called the folks at Horizon (Horizon Fuel Cell Technologies) in Chicago, told them what we’re doing, to see if we could get more power from our fuel cell. They had their tech team talk about it, but said he didn’t think he could get us a new one. About 15 hours before we were scheduled to fly out to Detroit, the Horizon rep called me back and said, ‘You’re not going to believe this. I found you a fuel cell – in the Czech Republic.’ If we could pay for the fuel cell in the next two hours, they would drop ship it direct to Detroit and it would arrive the second day we would be there.”

“It took a little doing, but we came up with about $10,000 with help from the University of Colorado – Denver, and ordered the fuel cell. Later I got an email saying it was held up in Customs because it didn’t have the right number on it. Several late night calls to Customs finally got the fuel cell released and it began the trip to Detroit, via Atlanta. Severe weather over the flight route between Atlanta and Detroit delayed the shipment even more.”

“To this point, the students didn’t even know a new fuel cell was coming, let alone all the obstacles that had to be overcome to get to this point. The students’ reactions when it arrived ranged from disbelief to shock that we all of a sudden had a new fuel cell, and finally great big smiles and fist pumps as they began changing out the power source. It showed up the next morning, and we spent half a day installing the new fuel cell in the car.”

Well, the team came in knowing that they may not complete the required course in time with the old cell. Would the new one do better? No time left to test and find out.

Time to run

Consider that, of the more than 100 teams that originally entered, only 89 of them passed inspections and were allowed on the track. Consider that the Wheat Ridge team was composed of high school students with no experience in designing and building anything, let alone a hydrogen fuel cell-powered car. Consider that the team had just spent hours on a last minute fuel cell change that they had not had a chance to test and had no idea of what performance to expect from it.

This was the stress load on the shoulders of these young men and women as the #218 Wheat Ridge High School entry made it’s way to the start line. But that stress would soon be relieved as the entry that started as a dream posted a best run efficiency of 151.5 miles per kilowatt-hour, nearly 40 m/kwh better than their second place competitor. That’s right! The young team from a small town in Colorado placed first in the Prototype Hydrogen category and went home with a $2,000 check, a huge trophy and bragging rights of having come to Detroit and taking it all their first time out.

What did the team do to celebrate? If you would believe now Junior Nate Rockenfeller, they hit the Hard Rock Café and flirted with the waitresses. But I think Sprague tells a more accurate tale when he told me that. “The competition was stressful. Right after we won there was a sense of relief; everyone was quiet and walked back to the paddock. We were all pretty well spent, went back to the hotel and then out to eat. Once we were cleaned up and out eating, their energy returned. The students started laughing, telling stories and having a great time, once again as a team.”

Will the team be back to defend its title in 2016?

Sophomore Casey Kramer, who dreams of designing cars one day with a goal of earning a degree in mechanical engineering at Colorado State University, filled me in on the goals for the 2016 competition. “We are building two cars. One will be almost the exact same as the 2015 car and competing in the same category. The second entry is for the Urban Concept category, a street legal car (miniaturized) complete with windshield wipers, headlights and taillights. Both will be powered by hydrogen fuel cells.”

To say this is yet another ambitious project would be an understatement. Fielding an Urban Concept hydrogen powered entry and getting past inspection would be a victory for these young engineers all on its own, considering that last year no fuel cell powered entry made it past this point. But having had a chance to speak to these young competitors, I have a feeling that their entries will do a lot more than just pass inspection. I have a feeling they’ll be coming home with two more trophies for the school’s display case. We at Motor Age wish them the best!

Want more information on the school’s success, how you can support their efforts or how to start a similar effort at your local school? Contact Mr. Sprague at [email protected].